We looked both from the outside in and from the inside out. We focused our attention on the center as well as on the margin. We understood both. […] Our survival depended on an ongoing public awareness of the separation between margin and center and an ongoing private acknowledgment that we were a necessary, vital part of that whole.

bell hooks

Abolition is a theory of change, it’s a theory of social life. It’s about making things.

Ruth Wilson Gilmore

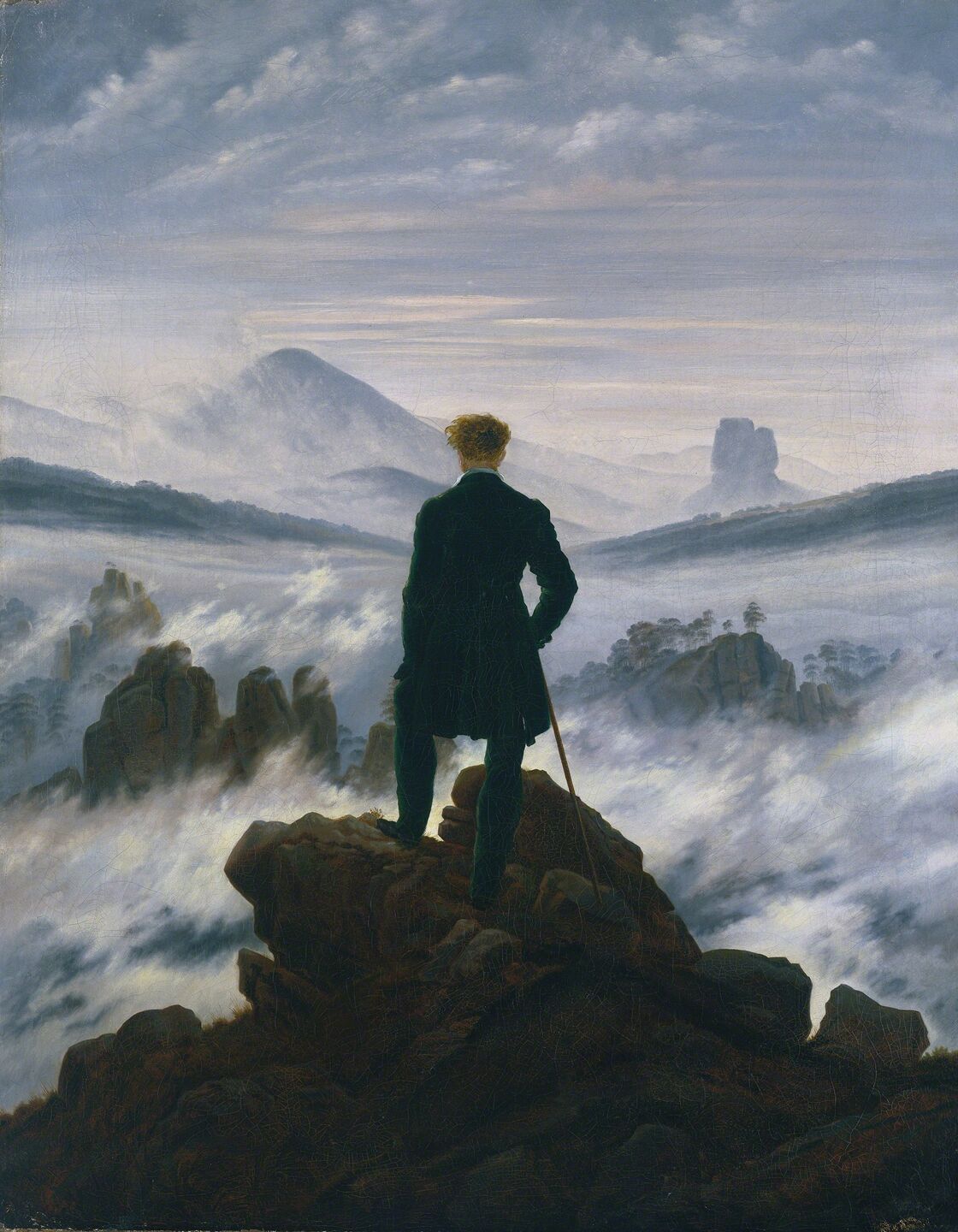

Solitary is a word often used in conversations about art that reference nature and the North American landscape. Coinciding with philosophical, spiritual, and literary shifts that took place in the early nineteenth century, the landscape paintings of visual artists like the German-born Caspar David Friedrich epitomized and invigorated a growing liberal imaginary, asserting that humans were autonomous and self-contained individuals. Perhaps the freedom to bear witness of that which exists in remote isolation, much like how these artists viewed themselves, encapsulated the purest expression of this liberal, ideological strain: to see the unseen for one’s self.

Individualism and self-reliance were also key tenets of the transcendentalist movement championed by literary figures like Henry David Thoreau, Ralph Emerson, and Walt Whitman, naturalists, writers, and philosophers who criticized the corruption of humans by the social institutions and governments intended to serve them. Of course, these white men—which included many self-identified abolitionists—were writing discourses on the importance of nature and the inherent goodness of people at the same time that the enslaved population in the United States, the majority of which worked on plantations in rural areas, was growing at an exponential rate. The privilege of having deep gratitude for nature, to feel as though one is “part or particle of God,” to experience life solitarily and not in coffle, was rarely, if ever, afforded to Black people living in the United States during this time.

Solitary is also a word that’s readily associated with the carceral state, prison population, spatial segregation, and torture. This association similarly originated in the nineteenth century, as solitary confinement was popularized as an alternative means of punishment in Quaker society. Countless research studies have concluded that solitary confinement has extreme psychiatric effects on inmates, especially for people already living with mental illness, which often goes undiagnosed for those deemed criminal. The lack of human contact and sensory deprivation can permanently affect the brain’s psychology. As just one example, a study conducted by the Journal of the American Medical Association looking at mortality outcomes for over 200,000 people released from prison between 2000-2015 in North Carolina, found that those who were placed in restrictive housing were 24% more likely to die in the first year after their release from prison. According to Vera Institute of Justice Program Associate Aaron Stagoff-Belfort, “The risk was particularly acute for certain causes of death; people exposed to solitary confinement were 54% more likely to die from homicide and 78% more likely to die by suicide. People who had been held in restrictive housing were 127% more likely to die of an opioid overdose in the first two weeks after their release.”

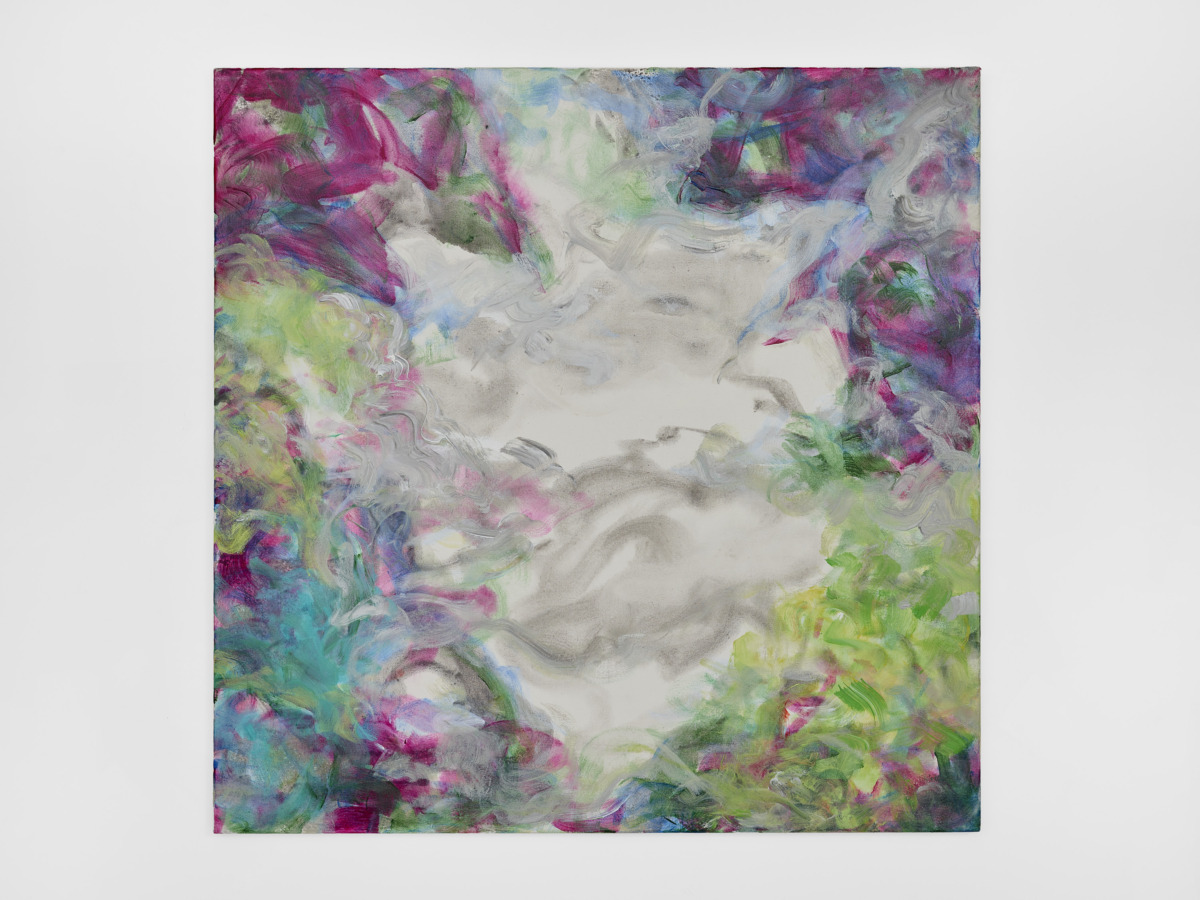

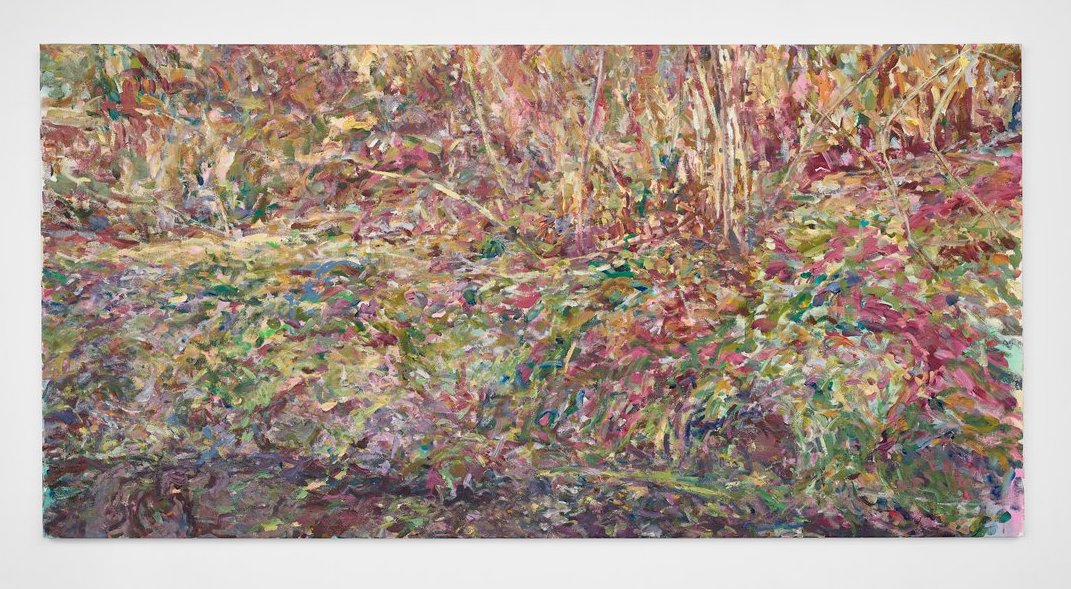

All things considered, Albert Woodfox, member of the infamous Angola 3, is a miracle. A strange statement but one that I hope provokes wonder. Maintaining his innocence until his death in August 2022, Woodfox, who was born and raised in New Orleans, and the late Herman Wallace were convicted of the murder of a corrections officer in 1972. Subsequently, Woodfox was ordered to serve a sentence that lasted for over forty-five years, forty-three of which were spent in solitary confinement in a high-security prison that occupies the same territory as a former plantation—”former” being the operative word here. He is the subject of a series of paintings by Oakland-based and Orange, Texas-born artist Foad Satterfield, an American painter whose landscape portraits—calling to mind the works of abstract expressionist phenom Norman Lewis—resist disciplinary and genre categorizations.

Earlier this year, I met with Satterfield on two occasions to discuss his Gulf Coast upbringing, artistic practice, and inaugural exhibition at the Malin Gallery in Aspen. The following interview has been edited for clarity and publication, and it is published in solidarity with Abolition Week 2023, organized by Scalawag.

Bryn Evans: Can you tell me more about your upbringing in the South?

Foad Satterfield: I was born in Orange, Texas near the Gulf Coast. The Sabine River separates Texas from Louisiana and runs through this border town. The Black side was small, about 25,000 people. And, of course, in those days, each community had its own economic zone, for the Black community it was Second Street. Many of the enterprises were initiated by my great uncle, Emile Barque, who came to Orange in the early 1930s as a young country boy The story goes that Emile couldn’t read, but he could count and measure. As a result, he bought a significant amount of land right on the river for a nickel an acre and built a restaurant, hotel, a dance hall, and a theater. I really regret that I didn’t pursue my elders for more of historical information about the area from my elders before they passed.

My family primarily spoke French at home. In fact, I did not speak English “well” until I moved to Lake Charles. When it was time for me to go to kindergarten, I went to school, but then they sent me back home. They said that I wasn’t ready. In a way, that gave me a reprieve from not being enculturated so early on. I was able to just be a kid and explore and grow. And most importantly, I was around these elders. By the time I actually began school, I didn’t really have an educational foundation, but I could sew, read a pattern and knit, since I learned it from my great aunt. I didn’t do well, and they kept me in first grade for another year. I didn’t want to do the work. I wanted to just go outside and find things and make assemblages.

My great aunt’s pilgrimage was pivotal for me. Bertha Barque, came from New Iberia, Louisiana. She had lived a sheltered life, was a devout Catholic and had never traveled. Very unexpectedly, in her fifties, she decided to go on a pilgrimage to Spain and Rome and stayed for six months. During this time Mamie sent several steamer trunks full of items she had collected on her travels to our house. Exploring the contents in these trunks—Christian paraphernalia, iconography, and artifacts—set my path toward becoming an artist. These treasures made me feel like I was in a personal museum.

BE: It was.

FS: Here I was in my living room, with all of these little precious things. Even though they would eventually be given to Mamie’s church to raise funds, I had full access to them first. This was a formative experience. Being exposed to these fascinating objects opened me to the sense of a larger world. I didn’t know what that meant but even at six or seven, I knew I wanted to travel and make things.

BE: It sounds like your childhood was very nourishing.

FS: Very rich.

BE: It makes me think about what happens when children have more of an opportunity to be free, when they have an opportunity to witness the world through their own eyes and aren’t socialized so early. Because it sounds like you were very observant as a child, and to me that’s one innate quality for an artist.

FS: I was able to be outside. The Gulf Coast is rich and its fertile. That verdant environment of organic material was so special to me. Something about it was magical, it was transformative. I was writing plays, even as a kid. I would build these little proscenium stages and take them beneath my great aunt’s bed. In those days, the beds were really high, three and four mattresses, so I would go under there and make these theaters. Then I started bringing candles under there. And I started setting fires.

[Chuckles] I would bring in little insects from outside to be in the plays. My parents and my grandparents never said no. Of course, they were mindful that I was using fire, and they didn’t want me to do that, but I wanted the dramatic effect. It is not lost on me that when I became the curator of the Dominican University gallery, where I taught for thirty-eight years, my expertise was in lighting. From that early age, I began thinking about how an object is best illuminated so that it may be felt and seen.

BE: I noticed that the word “light” was frequently used in the press release, as I was perusing through the different works featured in the Barry Malin exhibition. Can you tell me more about your relationship with light? I would love to hear your take on how the incorporation or manipulation of light operates in your paintings?

FS: Without light, in my opinion, the work would be intangible. There is the quality of light within the interior of a painting, and then there is the light necessary to be able to see the work reflected. So there are two different things going on here. I use light through the concept of chiaroscuro, which is light and dark, developing the dramatic, dynamic effect of the pictorial drama within the painting. I’m trying to lure you to come to this piece. When you come to the piece, whatever the reaction, that’s between you and the object. The light is fundamental.

BE: How do your experiences as a curator also inform your artistic practice?

FS: I set up my studio like a gallery. I’ve been to museums all over the world. I’ve seen great paintings under bad lighting, and I’ve seen great paintings under very good lighting. Often, when my paintings go into galleries, I can’t go in and control the space’s lighting, but what I can do is create the painting in such a way that it is astutely situated, so that no matter the light source, it will read and work. Being a curator has made me a little more acute to how light works.

BE: Would you say that an eye for lighting is one trait that a great curator possesses?

FS: I think it’s one of them. There are curators who are conceptual, intellectual organizers of artwork, which is valid. And then there are those who design exhibitions. That’s what I do as a curator, you see?

BE: Yes, and I find that a lot of larger institutions view those two roles as separate. There will be an exhibition design team and a separate curatorial team.

FS: Absolutely. And when they come together, it’s an amazing thing.

BE: My next question follows this thread on viewing, or the way in which we see things. When it comes to abstraction, there is sometimes a fear of “getting it wrong,” or not necessarily understanding what one’s seeing. Thus, viewers may put up a guard when viewing the work.

FS: Yes, yes.

BE: How do your works communicate or reach that subset of people?

FS: Bryn, I think I present a conundrum to many art professionals and viewers because I’m African American. If someone doesn’t know this about me, then they are curious about the work for its own sake. If they do know I am African American, they may be confused because my work is not narrative, you don’t see the figuration. But at the same time, there’s a very personal narrative present in the work, in the way that it’s made, if you can read it. You must have a certain level of sensitivity and openness. I use elements and context from the living world as an invitation, as a doorway to the work. I’m not trying to do landscapes, but it’s the invite. One of my colleagues helped me explain my work by framing it as abstraction with a landscape in front.

It’s created like a symphony or any other composition where there are many parts that must come together, in some kind of orchestration and harmony. I want to make work that anyone in the world could come in and look at. They may not understand or recognize it, but they can have some sort of resonance with what they’re experiencing by being in front of it. If I can do that, then I feel that my work is successful. I love the materiality, the physicality of things. Before I knew I wanted to be an “artist,” I wanted to be a fashion designer because I had no exposure to this thing called visual arts. However, there was couture. I wanted to go to fashion school in New York, and that’s the one thing my parents didn’t let me do. When we all graduated, people were going off to university, and I figured that I would go to university, too. Nonchalantly, I declared art as my major. That’s where it started.

BE: I have always had a fascination with Black artists who are interested in subject matter that isn’t mainstream, and how that functions as another level of marginalization that they now have to contend with. How do they find their clientele, their collectors? How do they find their audience when they’re not “who a Black artist is expected be”? It makes me think of Ralph Ellison. In the introduction to Invisible Man, he spends a lot of time discussing light, and what light means to him as someone who is often rendered invisible. In a way, abstract Black art is exceptionally political, because it provokes a different way of seeing that’s almost veiled to the untrained eye, in the ways that W.E.B. Du Bois theorizes and Ellison illustrates. Abstract art is less approachable, less tangible, thus making it not as easily commodifiable.

FS: I can’t let what’s going on in the marketplace determine what I do. Institutions attempt to press you to be in this particular kind of system and define yourself in a particular way.

BE: It can be applied to art and to artists, but also just life in general, understanding what someone wants versus what you actually want to give. An artist can stay so fixated on what is wanted, to the point that they become disconnected from what they actually want to produce, what they want to give.

FS: And that becomes the commodification of your sensibility. That’s not worth it. For me, it’s the long game. I’m always asking myself the question: Why am I doing this? What am I doing this for? As many things that have happened to me and my family, I can’t end with the negativity. I have to work for something larger, and what’s larger than self-expression? Art offers us immeasurable possibilities. It’s never lost on me. That’s why I cannot put myself in a constricted structure.

BE: Albert Woodfox inspired a series of your paintings, and in the past you’ve mentioned his profound impact on you. Can you tell me more about his life and the works he inspired?

FS: Albert Woodfox’s story is about re-constituting oneself, recreating oneself, finding a place within oneself that has nothing to do with external stimulus whatsoever. There weren’t many opportunities for Black youth in New Orleans when Woodfox was growing up there. He was incarcerated as a young person, and once he entered the prison system, he circuited through it for most of his life. When Woodfox was in Angola, a guard was killed. Although he consistently denied any involvement with the crime, and the evidence pointed toward his innocence, he was charged and convicted as being associated with it. He served a sentence that lasted for over forty-five years. He spent forty-three of those years in solitary confinement, which was and still is unprecedented. Because he was organizing with the Black Panthers at the time, to provide his fellow inmates with tools to bolster their internal sense of self-worth and human dignity despite inhumane conditions, there are theories that the law enforcement wanted to make a statement with the length of his sentence. Woodfox was considered a threat because he tried to challenge the status quo of prison culture. So, he was isolated to break his spirit. That’s what solitary confinement is about, the deterioration of human will. Just think about that for a moment. His story also touched me because we were about the same age. I think I’m a few years older than he was, but I grew up in Lake Charles, which is similar to New Orleans. When I met him at the Black Panthers convention at the Oakland Museum and had the opportunity to give him a copy of the monograph, that was a highlight of my life.

The Woodfox series is dedicated to that profound struggle of preserving one’s humanity. I created the works horizontally, because I wanted the story to be read as a narrative—that during the time Albert Woodfox was in solitary confinement, nature was still being nature outside, doing what it does. It’s very difficult to talk about, but the works are subtle monuments to something that’s greater than conditions. Although these works were conceived as a tribute to a particular person and his particular circumstance, they address the metaphysics of life, how the seen and the unseen work in tandem.

BE: I’m just so struck by this very profound tribute to someone who wasn’t able to see outside for over forty years. The fact that Woodfox could become the subject of “a landscape painting” is very, very radical, in my mind. And when we’re thinking about abolitionist and carceral geographies, or vanguards like Ruth Wilson Gilmore or Angela Davis, for this series to add to that entire canon is so unexpected. The elusiveness of his last name, being also tied to the natural world, if you’re not aware of his personal history, it won’t come across.

FS: That’s right. In the monograph, the section dedicated to him was called “Heartwood.” Heartwood is the most internal part of the tree, the softest, most tender part. There are so many metaphors.

I remember after Woodfox had given his talk at the Oakland Museum, I went up to him, and he was a very gentle, quiet guy. I gave him the book, and I could tell he didn’t know what to make of it at first. [Chuckles] I said, “Take this, and when you have a chance, just look at it. I’ve really appreciated your talk, your time, and your efforts in encouraging the younger inmates.” And as a result, I feel a responsibility to use my training as an artist, not just to make beautiful painting, but to create works that are profound statements for how we can see and imagine the possibilities of freedom.